Zero-Storage Data Publishing on Ethereum

Taking advantage of off-chain monitoring

What’s the cheapest way to publish data while maintaining an unchangeable, permanent record of having done so?

Blockchain?

What’s the most expensive way to do computing today?

Blockchain?

Actually this second point may or may not be true, but one thing is true, if the blockchain is expensive, storing data is the reason why. Any data.

In this article we will recount our experience trying to create a simple one-way publisher-to-consumer data delivery smart contract. At the same time, we’ll explain an idea we have called off-chain monitoring and how our project, TrueBlocks™, helps us use this idea to lessen the cost of running a smart contract.

Off-Chain Monitoring

TrueBlocks allows us to monitor Ethereum addresses in real time. We initiate a monitoring session with a simple command:

chiffra init <monitor_name>

(Chiffra is a command line tool that builds off-chain monitors.)

Given the above command, the system first asks a few questions (What addresses to monitor? When they were first deployed?) and then generates C++ code and builds the new off-chain monitor.

The first time the monitor runs, it syncs to the locally running blockchain node, optionally caching the data as it goes. It then begins periodically pulling new blocks from the node.

If the monitor finds a transaction (either an external or an internal contract-to-contract transaction) either to or from one of the addresses we’ve indicated, it responds.

By default, the response is to simply display the transaction to the screen. However, we can modify the monitor code to do anything we want. For example, it could keep a daily list of transactions and email us a summary of the activity on the contract at the end of each day.

TrueBlocks is a customizable, per-account, fully-decentralized blockchain scraper. This contrasts with centralized scrapers, such as the EtherScan, in that the data (once it arrives at the node) comes straight from the node as opposed to from a third party.

The monitor programs do whatever we want them to do. For example, they can easily write transactions to a database (for later use in a website, for example). If a non-technical user, such as an accountant or auditor, needs the data, it can be written to an Excel spreadsheet. We’ve even written one monitor that duplicates the token account balances of an ICO — on the fly and off-chain.

The monitoring is done locally and off-chain and per account. The data is as fresh as a fall pear pulled directly from a tree.

Monitors understand the data they are retrieving. By this we mean the monitor re-articulates the data in the language of the smart contract that created it. It does this by fetching the ABI file of the contract and using that to translate the node data. **0xc9d27afe** becomes **vote.** **0x23b872dd** becomes **transferFrom(a, b)**. TrueBlocks turns ugly blockchain data back into human readable and easily understood information.

Recently, I was developing a smart contract, and I realized I was thinking about my work in a new way. I was writing my smart contract anticipating that it would be monitored. The monitor component had become an integral part of the smart contract system I was writing.

And the more I’ve explored this idea, the more I’ve discovered how powerful it really is. In this post I examine one example of what can be done with off-chain while still decentralized monitoring of smart contracts.

The Price of Ether is Too High

You may have noticed that the price of ether has skyrocketed recently. Some people look at this as a good thing, but it’s also a bad thing because it dissuades people from using smart contracts. The more expensive a smart contract becomes, the less likely people are to use it. The silver lining is that it makes developers pay attention to cost efficiency.

Here’s a recent comment on stack exchange:

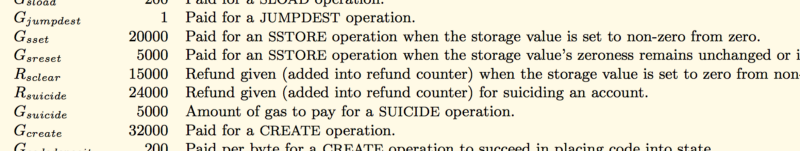

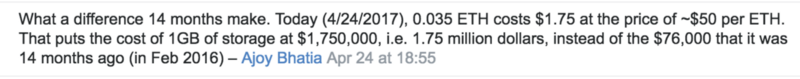

While one can reduce the operating cost of a smart contract by lowering the gas price at each transaction, it still costs more than $1,000 to store a single MB of data. That cost has nearly doubled recently! Storing data directly on the blockchain is not, and never has been, a viable solution.

The smart contract I was originally writing tried to deliver data using a very basic publish/consume model. In the first version, an automated off-chain system posted data to a smart contract, and our users, running a “sister” system on their computers, would pull the data from their local node. What’s the most expensive thing to do? Store data. Not good.

Publishing Data the Old Fashioned Way

Greatly simplified, our first drawing board implementation looked something like this:

publishData(address userAddr, string theData) onlyOwner {

dataStore\[userAddr\] = theData;

}

where dataStore maps from a user’s address to the published data. It was simple and easy to understand, but it was also astronomically expensive, especially given the nature of our data which was big and unruly.

An obvious improvement, and probably something we should have thought of from the beginning, was to store the data on IPFS and publish only the IPFS locational hash to the smart contract. This is a common pattern used by many Dapp developers.

In this version, the off-chain publishing system writes the data to IPFS (and receives in return a locational hash). It then posts that hash to the smart contract. The sister software, running on the client’s machine, retrieves the hash and accesses the data from IPFS.

Again, greatly simplified, that code looks something like this:

postData(address userAddr, string ipfsHash) {

dataStore\[userAddr\] = ipfsHash;

}

But the system was still storing data on the chain.

Hashes are Good, But not Good Enough

The hash of an arbitrarily long piece of data is generally shorter than the data itself. This was especially true of our data. Publishing a much shorter, fixed-length hash was significantly cheaper. Plus it had the added benefit that we could easily calculate the future cost the system and model that cost as the system presumably scaled and the price of ether fluctuated.

This second version of our system was cheaper, but the price of ether kept rising: $60.00, $70.00, $100.00. We needed to profoundly rethink our methodology.

Smart Contract Monitoring to the Rescue

For the next version of the system, we eliminated on-contract data storage all together. We wouldn’t have thought of this method had it not been for our work on real-time monitoring. We realized the monitor program itself could become an active part of the system (as opposed to being a passive observer).

So we re-wrote our smart contract to store zero data. The only thing the smart contract does now is provide an interface to generate events. This is a simplified version of our latest contract:

pragma solidity ^0.4.11;

contract DataDump {

function postData(address recipient, string hash) {

DataDumped(recipient, data);

}

event DataDumped(address indexed recipient, string dataHash);

}

The data we deliver is time sensitive, therefore, when we have something to publish, we simply write the data (in plaintext) to IPFS. IPFS returns a locational hash of the data.

Off-chain, we’ve previously acquired the end user’s public key during the sign-up process, and we use this key to encrypt the locational hash. We do this because if we didn’t, and simply published the hash to the blockchain, anyone could easily find the data. We want only particular users to find particular data. Of course, there’s nothing stopping him/her from sharing the hash, but this was not a problem for us given the nature of our data.

After writing the data to IPFS and encrypting its location, we initiate a transaction on the blockchain. This creates an immutable record of us having published the data without incurring any blockchain-related data storage costs. If, later, the user claims we did not publish the data, we can prove that we did.

Lessen $1,000 per megabyte data cost? Check. ✓

The sister monitor, which is running on the end user’s machine, notices the transaction and responds by pulling the encoded IPFS hash from the event logs. The hash is then decoded and the data retrieved. From here the user does whatever they wish with the data.

For the time being, we bill our clients for the service using an external system unrelated to the publishing contract. If the customer doesn’t pay, we simply don’t publish for that user. If the customer wishes to discontinue our service, they simply remove their payment information from the payment system.

Why Use a Blockchain?

An obvious question is why use a blockchain at all?

First: it’s fun.

But more importantly, if the user claims we didn’t publish the data, we can prove that we did. The user cannot claim we didn’t publish the data; if the transaction is on the chain, and it appears on IPFS, it was published.

Why Not Just Use Web3.0?

You could. TrueBlocks does not replace Web 3.0. But we think it enhances it. There’s nothing stopping you from using Web 3.0 to accomplish the exact same task, unless, that is, your time and your desire to get complete data matters to you.

Both TrueBlocks and Web 3.0 use the Ethereum node’s RPC interface to request and process the data. TrueBlocks improves on what is returned by the RPC in the following ways:

- TrueBlocks creates a cache so that the second and subsequent times one requests data, it is delivered 80–100 times faster. It’s also faster on the initial retrieval because it’s written in highly optimized C++ code.

- The initial transaction data returned by the RPC is incomplete. It does not include an ‘error’ flag. Nor does the returned data include contract-to-contract incoming transactions into an account. TrueBlocks corrects these shortcomings.

- The RPC returns un-articulated data (that is, bytes). Your Web 3.0 code must translate this hex data back into human readable form. TrueBlocks does this for you automatically (if given an ABI).

Is There Anything Interesting Here?

What we’ve described here is a data delivery system that stores zero data on the blockchain. And yet, the system is able to prove individual publishing events on a per user basis. Also, what was formerly a cost for the publisher, now may potentially be a source of income (see filecoin).

Will it work? Maybe not, but we’re working on it. Join us at GitHub.

If you find our work interesting and would like to learn more, please visit our website at (http://trueblocks.io). Sign up for our news feed. We’ll keep the ideas coming.

Support our work? 0xf503017d7baf7fbc0fff7492b751025c6a78179b