Smart Contracts are Immutable — That’s Amazing…and It Sucks

Write once, modify never

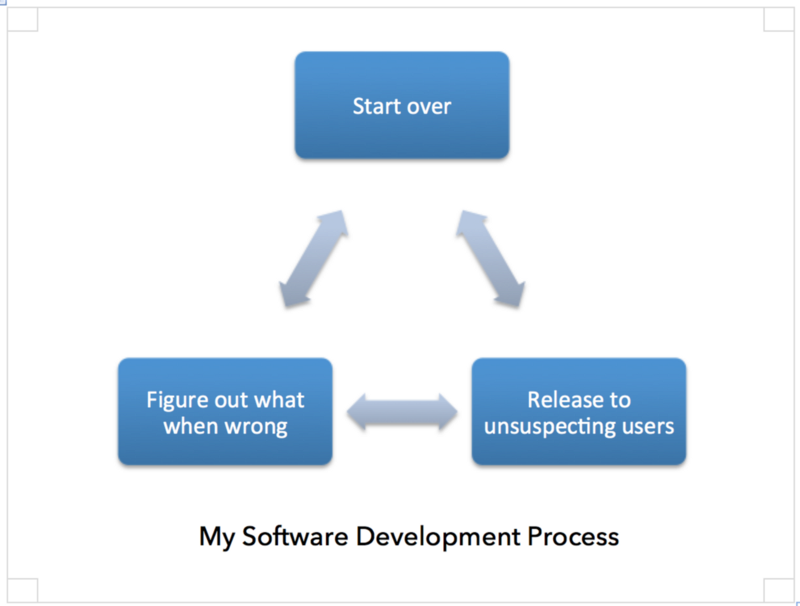

Apparently there are two types of software engineers in the world. One type writes code, pushes it out into the world to see how it works, keeps track of the bugs, and then goes back to drawing board, re-writes the code, fixes the bugs, and re-releases. Write-release-fix, write-release-fix. A never-ending circle.

The other type of software engineer seems to be able to write code once, and because it was carefully planned and carefully implemented, it runs correctly forever. Write-release-done.

I should probably not admit this, but I am not this second type of programmer. At least, I didn’t used to be. Now that I’ve started learning the smart contract programming language (Solidity), I think I’m going to be forced to change my methodology.

Recently, I wrote a smart contract for what I believe to be the world’s first Ethereum Early Adopters Registry (EEAR — pronounced “ear”). What is an EEAR? Have you ever driven down the streets of your town and seen those little signs in the store windows saying, “Doing business since…”? That’s the idea behind the EEAR. Twenty years from now — hell — two hundred years from now — you will be able to send your customers to the EEAR to prove that your company was an early adopters of Ethereum. (Check it out.)

How do I know you will be able to come back two hundred years from now and the EEAR will still be running? This is one of the most interesting things about smart contracts. They run forever. Once a smart contract is deployed, it will run at exactly the same address for as long as Ethereum exists. That’s not the only thing. The smart contract code running at that address will never change. How is this possible?

It’s All in the Address

In Ethereum there are two types of accounts. If you own any ether at all, you’re already familiar with the first type of account. It’s where your ether is. The other type of Ethereum account is called a smart contract. A smart contract can hold ether in the same way a regular account does, but it also has software code associated with it. Every account (both regular and smart contract) has its own unique addresses on Ethereum.

When you’ve completed your smart contract code, you deploy it onto the Ethereum network. Deployment means the contract is compiled and then “stood up,” so it can run. The smart contract is located at its address, now and forever.

The address of the newly deployed smart contract is created by hashing together the address of the deploying account and that account’s transaction counter called its ‘nonce.’ (Note: there are other things involved unimportant to the current discussion). The nonce is incremented each time an account initiates a transaction.

Because the nonce changes with each transaction (a contract deployment is a transaction) the resulting Ethereum addresses are unique. In fact, the way the hash function works, each new address is wildly different than the one before it. This is why I say that the smart contract runs forever and cannot be changed. Even if you wanted to (and I almost always do, given the way I write software), there is simply no way to re-deploy a contract to the same address.

If the Internet worked the way Ethereum does, and I changed my website http://ethrilleum.com, the re-deployment would move my website to a new address. Who knows, perhaps http://no-one-will-ever-find-me-again.com.

Why is this Amazing?

What makes smart contracts so amazing, in my opinion, is exactly what I’ve described above. Once a smart contract is in place it will stay there forever. Not only that, the code at that location will never change. This allows an end user to trust the software perfectly. No-one will ever again be tricked into using software that does something untoward behind the scenes. There are no scenes. The software is what the software does, Forest.

I didn’t mention this earlier, but before you ever agree to participate with a smart contract, you should insist on seeing its Solidity source code. The counter-party should be happy to provide it to you. If not, do not do business with them. With their source code, you can compile it, and then pull the code behind the address they’ve given you off the block chain and make sure it’s the same. If the source code they’ve provided is not identical to the code behind the address — by jot or a tiddle — don’t interact with it.

I’ve visited many of Solidity Dapps (distributed applications running Solidity code) over the last few months (see The State of the Dapps website). Some of these sites make their source code very accessible. And while it is not easy, you can confirm that the code they say is running is actually running. These types of sites provide all the information you need to generate the byte code and verify that the code behind the address is what it says it is. (This process should be easier than it is, but that’s a different story.) Other Dapps provide no information at all about their source code. I would not interact with such a Dapp. Who knows what they do with your ether?

Assuming you can verify a contract, and you can read the source code, then you then know exactly what will happen when you sign up. Once you start interacting with the contract, that contract will always be there, and it will always behave exactly as it’s programmed.

That’s amazing. That’s something totally new that never existed before. But it also sucks. Here’s why.

Why Does it Suck?

When I first started writing my EEAR code, I made a mistake. My contract keeps a list of registrants (obviously — it’s a registry), and in an effort to be generous and share some of the income from the contract (of which there has been about $3.50 US), I wrote a bit of code that looked like this:

myShare = msg.value; 1

owner.send(myShare); 2

uint amount = (msg.value-myShare) / numRecords; 3

for (uint k = 0; k < numRecords; k++) { 4

records[keys[k]].owner.send(amount); 5

} 6

This code contains at least two serious errors. Can you spot them?

First, it sends all the ether to me — I am ‘owner’ because I deployed the contract. Secondly it spins through each existing registrant and gives zero dollars.

The first error is apparent in line 1 where (myShare = msg.value). At its best, this is selfish, but I could argue that it’s not incorrect. Nowhere on the EEAR website does it say I would share revenue. My end users could read the source code and verify it if they wanted to. Read the fine print, baby!

In fact, this was just an honest mistake. I meant to put a value like 50% in there, but I forgot. I would have fixed it except for the immutable / immortal thing I’ve described above. By the time I noticed this first mistake, I already had ten users.

Worse, I had no way of getting in touch with them because I didn’t ask them for an email addresses when they signed up. Worse yet even, I couldn’t change the code because the modified contract would be deployed to a different address and they would never find me. I was stuck.

But then I fully realized why immutable/immortal code — for all its amazing benefits — sucks (and I say this lovingly — in the end, I think the positives far outweigh the negative).

If you look carefully at the above code, you will see that as the list of registrants grows, the number of times the ‘send’ function in line 5 is called with a zero value grows in proportion.

My lovely smart contract, of which I was so proud, was a total idiot!

Every time the ‘send’ function gets called on line 5, it lays a transaction on the network, and — importantly — the contract has to pay ‘gas.’ Ethereum runs on ‘gas.’ ‘Gas’ is why the miners mine. My brilliant, amazing, never-to-be-changed, never-to-be-removed, smart contract was going to eat me out of house and home!

So now what was I supposed to do? My only recourse was to write down each of the participant’s account addresses, the time and date they joined the registry, the amount they paid to join, and the comment they made to posterity. I then had to go back to the drawing board and modify my code to fix the problems. (I found other problems as well — I told you — I’m that type of programmer.) I then re-deployed my contract to a new Ethereum address.

Of course, being brand new contract, the new registry was empty. I had to hand enter the ten records, and luckily I built in functions to transfer the ownership of the records to the original registrants’ account.

This still didn’t solve my problem entirely because the old contract was still running at its old address. Luckily, I had built in a ‘kill’ function in the original code. So, after I had everything transferred, I called the ‘kill’ function to remove the old contract.

Lessons Learned

I learned a couple of useful lessons as part of this adventure:

- Make sure to get your solidity code right the first time.

- Always include a ‘kill’ function in your code. If you don’t and the contract is what I would call a “eater of houses and homes,” it will run forever and drain your account. (You can, obviously, simply drain the account yourself, and then the contract will run out of gas each time it’s called — but that sounds like the act of a bad citizen).

- Carefully consider capturing email or other contact information from your clients in case you have to bring the contract down. In this way, you can at least let them know of the new re-deployment address.

- Build in an export / import capability so that any possible future transition to a new contract is easier. I might write a post later about that.

I hope this short tale of my mis-adventures into the world of Solidity was entertaining. Let me know what you think in the comments section below. And visit my new and improved EEAR 2.0 when it becomes available. It no longer even pretends to share the revenue with the user, but at least it won’t bankrupt me the way version 1.0 was designed to do.

Chao.