It’s Not That Difficult

All about the Ethereum difficulty calculation

All about the Ethereum Difficulty Calculation

Special thanks to a first-rate Tuftian and data scientist, Ed Mazurek, for early versions of the R code used in this article.

Each time the Ethereum time bomb goes off, two related questions arise. The first question (and arguably the more important) is, “When will blocks get so slow, they will be intolerable”. The second question is, “How long should we delay the bomb this time?”

In this short article, I present a very simple — almost trivial — solution to the second of these two questions. My proposal for how long we should delay the time bomb is “given a hard fork at block N, delay the difficulty bomb for N blocks (or a few less for added safety).”

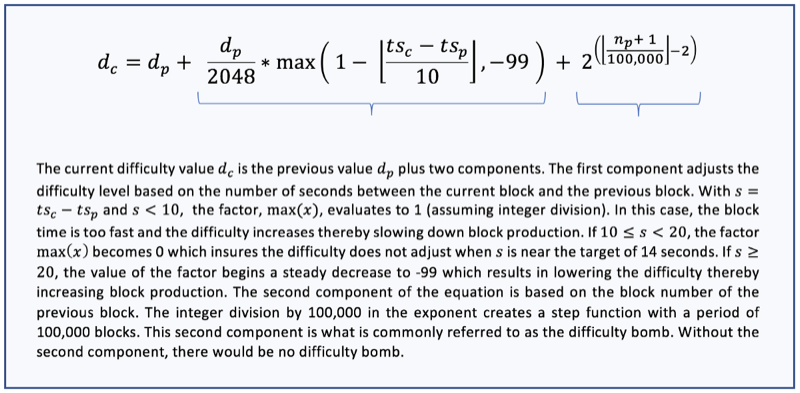

I won’t explain the difficulty calculation in this article (see my previous article). This image, which shows the calculation, appears in that article:

Looking closely at this equation, notice that it is composed of two parts.

The first part I will call the “adjustment” (or part A). This portion adjusts the current block’s difficult to account for the timing of the previous block. This adjustment either lowers the difficulty or raises it depending how long the previous block took to appear. This component is highlighted by the first bracket above. Spend some time figuring out how it works. The effect of part A, which works exactly as it’s designed, is to squelch changes in the hash rate. The charts below make clear that this section of the calculation is working correctly.

Because part A works as designed — eliminating effect of hash rate — I will argue that worrying about hash rate when reasoning about delaying the time bomb is unnecessary. To say this another way — a too-low hash rate cannot make the bomb any worse than it is, and too-high hash rate mitigates the effect of the bomb. This leads me to conclude that part A of the equation is unrelated to slowing block times. The second part of the equation (part B for bomb) causes all the trouble.

It’s possible, as I do below, to separate these two components. This makes it much easier to see that part A has no effect on block production while part B—the bomb — dominates when it manifests itself. Additionally, I will show that diffusing the bomb is easy. One simply needs to set the period back to zero each time one forks the chain to diffuse the bomb.

Generating and Formatting the Data

As is usually true when dealing with data, we start by acquiring data. We used our own software library, TrueBlocks, to write the following code:

# include “etherlib.h”

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

init_etherlib();

for (int i = 0 ; i < getLatestBlock() ; i++) {

CBlock block;

getBlock(block, i);

cout « block.blockNumber « “,”;

cout « block.timestamp « “,”;

cout « block.difficulty « end;

}

}

…which generates a very simple .csv data file of this format…

blocknumber, timestamp, difficulty

0, 1438269960, 17179869184

1, 1438269988, 17171480576

2, 1438270017, 17163096064

…

8981997, 1574448913, 2432407853358678

8981998, 1574448935, 2432545292312150

8981999, 1574448985, 2427931666241578

8982000, 1574449029, 2424512564668329

Along with a list of daily hash rates that we got from EtherScan, this is enough to understand Ethereum’s difficulty calculation. We use RStudio and a data programming language called “R” to build the following charts. If you’re not familiar with “R”, you should check it out. It’s fantastic.

We’ll start by looking at the Ethereum hash rate.

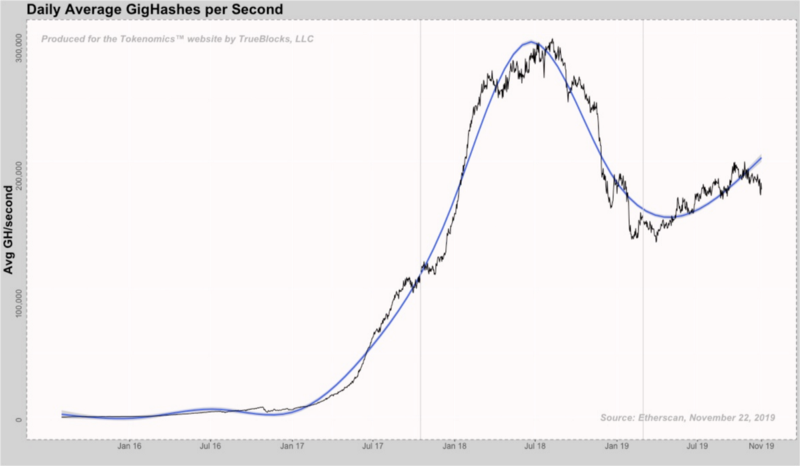

Daily Average Hash Rate

The data in the first chart comes from EtherScan. It shows Daily Average Hash Rate for the Ethereum mainnet. I cannot vouch for this data, as I don’t know how it was created, but I assume it’s okay. Here’s a link the data.

Discussion:

Apparently, Ethereum’s hash rate follows Ethereum’s price. This chart reminds me of an Ethereum price chart. The rate of growth of the hash rate skyrockets during the summer of 2017 and peaks during the first quarter of 2018 (just like price). The bump in October of 2016 is the infamous 2016 DDos attack, and the two vertical grey lines are the Byzantium hard fork (Oct. 2017) and the Constantinople hard fork (Jan. 2019). There’s not a lot to say about this chart, but we will refer to it as we discuss the chain’s difficulty data, below.

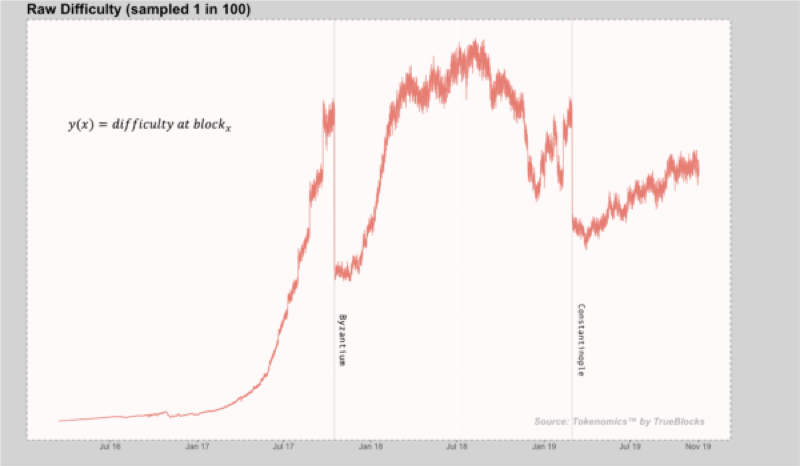

Raw Difficulty Data

The first chart based on difficulty data shows data returned from Parity’s RPC call get_Block. First, some standard statistical information:

**Summary Statistics for Ethereum’s Difficulty **0,016,970,000,000,000 — Minimum 0,111,700,000,000,000 — 1st Quartile 1,926,000,000,000,000 — Median 1,649,000,000,000,000 — Mean 2,687,000,000,000,000 — 3rd Quartile 3,702,000,000,000,000 — Maximum

Our first chart is pretty straight forward:

Discussion: The data was produced at block 8,920,000, and while “R” can pretty easily handle that many records, given the iterative nature of data exploration, we choose to sample one record out of every 100. This give us around 9,000 records which are presented in the above chart. The same grey vertical bars showing the hard forks in this chart as well.

The height of the red line, y(x) = difficulty at block.x represents the difficulty at the time of the given block. It’s easy to see the effect of diffusing the difficulty time bomb at each fork. The DDos attacks in the Fall of 2016, and, referring back to the hash rate, you may also see a relationship between difficulty and hash rate.

Pretend the time bomb had not been diffused— in effect push the red line up as far as the bomb diffusion pushed it down — do this for both hard forks and you can almost see the same shape as the hash rate chart. In other words, hash rate and difficulty are tied together. This makes perfect sense. This is exactly what part A of the difficulty calculation is designed to do. It’s designed to adjust the difficulty in direct response to varying hash rates.

The behavior of miners probably doesn’t change because of a difficult bomb diffusion. Their mining rigs continue to run identically before the diffusions as after them. The only thing that changes is the time between blocks, on average, lowers.

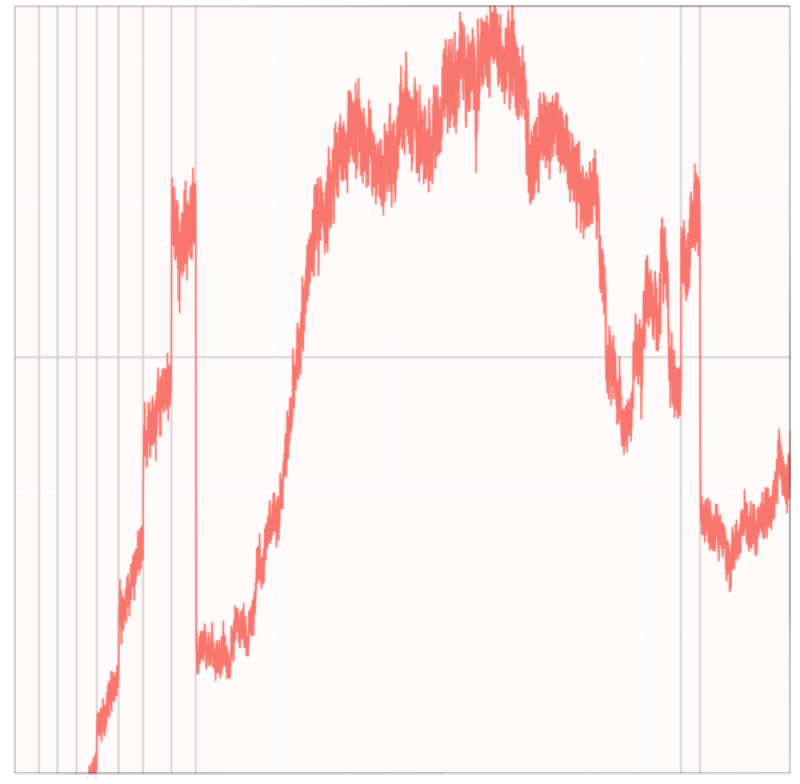

Before we leave this chart, notice something else. Look carefully just prior to the Byzantium hard fork. You’ll see four or five single-line, vertical jumps in difficulty level. In fact, the jumps are twice as large each time they appear as the previous time they appeared. These jumps are the time bombs. Let’s focus more on that area of the chart:

Discussion: We’ve inserted vertical lines at each 100,000-block boundary. Notice, just prior to the hard fork, the jumps in difficulty land exactly on the markers. In between the markers, the difficulty continues to go up, but nowhere near the speed as on the markers. The inter-explosion increases are consistent with the fact that the overall hash rate was raising very quickly at this time in 2017.

You may also noice that each successive ‘bump’ — each time the bomb explodes — it explodes twice as high as it did the previous time. The periodic nature of these jumps, it turns out, become important in understanding what’s going on.

In the remaining charts in this article, our goal will be to separate the first part of the difficulty calculation (part A or the “adjustment”) and the second part of the calculation (part B or the bomb). This will help us understand how to handle the bomb in the future.

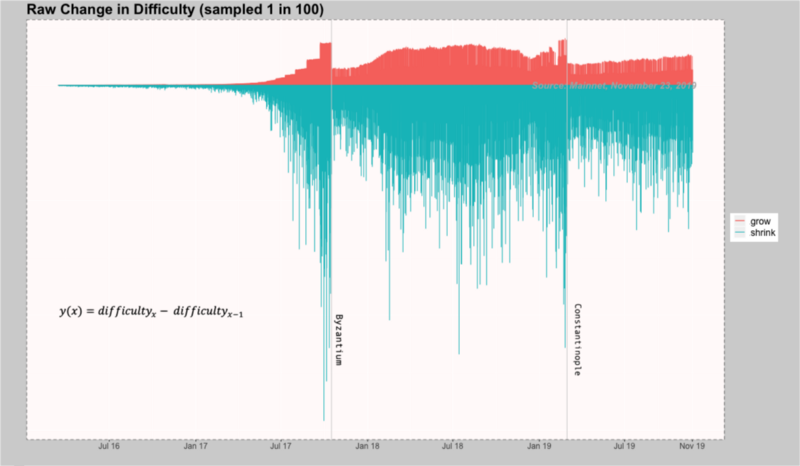

Per-Block Changes in Difficulty

In the next chart, we look at the change in the difficulty between each successive block. That is y(x) = diff_block_x — diff_block_x_minus_1.

Discussion: As we mentioned above, part A of the calculation ‘hovers’ around a difficulty level geared towards ensuring 14 second blocks. This ‘hovering’ is revealed in the above chart by the red-blue nature of the data. The ‘grow’ part of the chart (red) represent positive changes in difficulty (i.e. difficulty gets higher, block production gets lower, and block times get slower). The ‘shrink’ values (blue) are negative (lower difficulty, faster blocks and more of them). The ‘adjustment’ hovers around zero. In other words, the calculation is trying to maintain ‘no change’ in block times. The part A calculation hones in on a value — 14 second block times.

On this chart, you may also, for the first time, clearly see the bomb exploding. And it’s arguably obvious that they are exploding twice as large each time they explode.

But I don’t think this chart is clear enough. Why, for example, does the same pattern not show up clearly during the Constantinople time period? It turns out the reason for this is because of the greatly increased hash rate. The calculation is able to maintain the 14 second blocks times, but the system is swinging back and forth more vigorously. The reason we can’t discern the same bomb activity near the Constantinople fork is because it’s being obscured by the wider fluctuations.

Is there anything else we can do to see more clearly? Yes, as a matter of fact there is, and we’ll show that in the next chart.

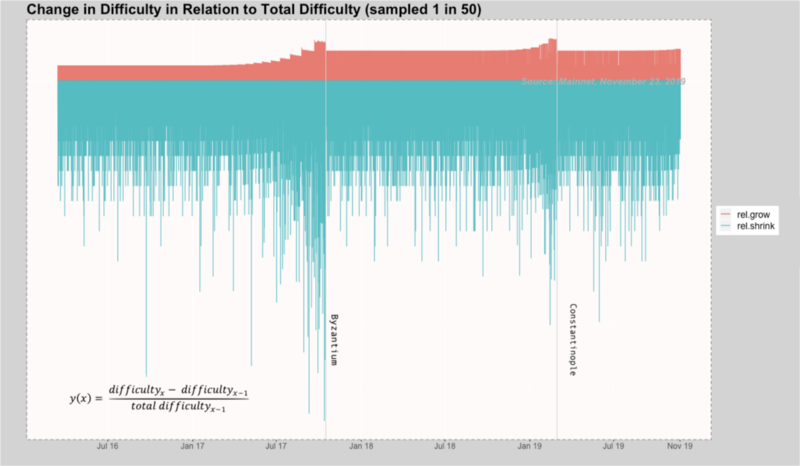

Relative Change in Difficulty

Our final chart in this part of the paper is a chart showing the change in difficulty relative to the total difficulty in the block. That is y(x) = (difficuly_x — difficulty_x_mius_1) / difficulty_x_minus_1. The previous chart shows the raw change in difficulty. This chart show a normalized change. This removes the growth in hash rate. It will allow us to clearly see the two different parts of the calculation, part A and part B.

Here’s the chart of per-block changes in difficulty over total difficulty:

Discussion: And now we can actually see why I said above that worrying about hash rate is counter-productive to a discussion of the difficulty bomb. You can see very clearly that until the time bomb ‘rears it’s head’ block production is not affected by increased (or lowered) hash rate. Part A of the equation maintains a steady state relative to block speed and production. Difficulty (on average and relative to itself) remains nearly unchanged up until the time bomb starts exploding.

Two interesting things to notice: (1) You can see the bomb starting to ‘rear its head’ at the right-most edge of the chart even though the distance between the appearances are much shorter than between Byzantium and Constantinople — I explain this below; (2) the striations at the bottom of the chart are an artifact from the integer division by 10 in part A of the calculation; (3) the higher hash rate appears to delay the ‘head-rearing’ as Lane Rettig noticed prior to Constantinople and we wrote about in the above mentioned article.

There’s a lot more I could talk about on this chart, and maybe some day I’ll come back to it, but I do want to make the case for a better way to diffuse the bomb in the future.

A Better Way to Diffuse the Bomb

First, I want to make the point that worrying about the hash rate while worrying about the time bomb is counter-productive. The effects of increase (or decreases) in the hash rate are removed by part A of the calculation. That’s what part A is for. And, it’s working nearly perfectly as is evidenced by the near-perfect flatness of the difficulty deltas (relative to its current height) is stable. Hash rate apparently has no effect on block time — but this is what we already know — this is what the difficulty calculation is designed to do.

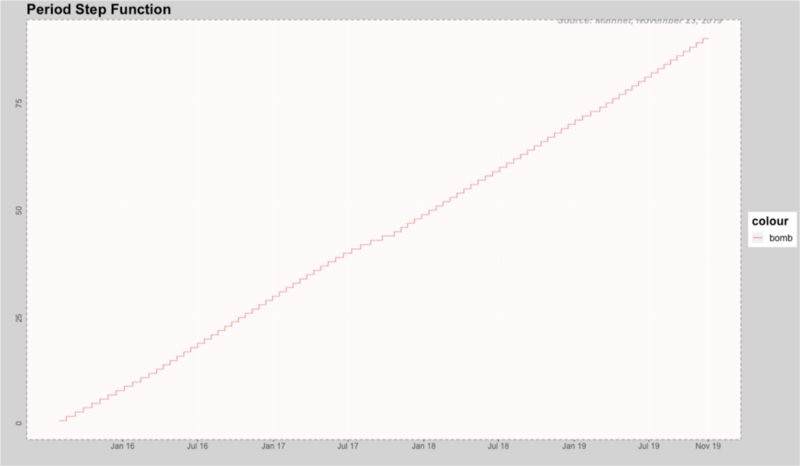

The bomb is defined in the above equation as an additional value added to the end of the calculation as

2 ** (floor(current_block_no / 100,000) - 2)

That is, two raised to a power. We can re-write this as 2 ** p allowing p = floor(current_block_no / 100,000). (We can ignore the -2 as it simply shifts the calculation to the left.) We’re left with a step function in p or period.

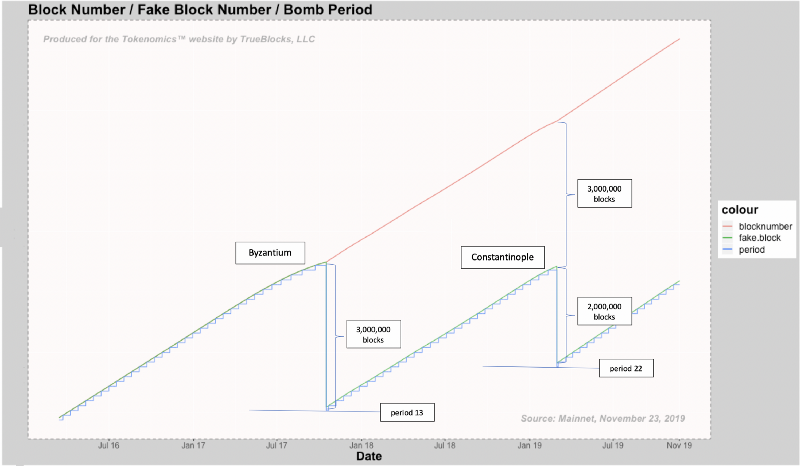

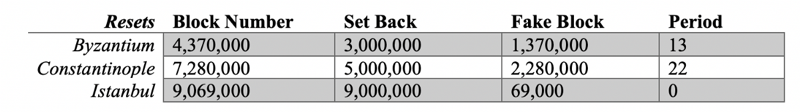

Remember though, that the core developers have twice reset the bomb — this means, quite literally, that they reset the period. The go code works by creating a fake block to be used in the calculation. The fake block appears to be in the past, which resets the effect of the bomb. Here’s a corrected chart showing what’s really going on with the period:

The true block number appears in red above and ranges from zero to 8,920,000. The fake block number (in green) tracks the real block number until Byzantium when it was reset 3,000,000 blocks to the past. It then runs parallel to the real block number until it gets reset again (this time by 5,000,000 blocks) at the Constantinople fork.

Here’s a table recounting the resets. Do you see anything odd?

The fake block after the Byzantium fork was 1,370,000 which, when integer divided by 100,000 gives a period of 13. That is, at each block an additional difficulty of 2**13 was added after the hash rate adjustment. By the time of the Constantinople hard fork, the period was reset to 2,280,000 which translates to period of 22, an additional difficulty of 2**22. This, I think, is why the time bomb is going off earlier than we anticipated. We didn’t reset it back far enough the last time.

The suggested value of resetting the time bomb this time is back to block 69,000 which translates to period zero. This is exactly the right amount to reset to.

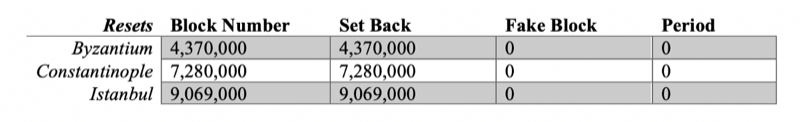

How to Better Reset the Difficulty Time Bomb

There’s a very easy way to reset the time bomb to the right value each time we have to reset it. This will make most of the problems related to the difficulty bomb disappear. Simply set the time bomb back the same number of blocks as the FORK_BLOCK_NUMBER of the fork (with a little bit of play). In this way, the fake block gets set near zero and the period will be zero.

Because the time bomb dominates the slowing down of block production this will have effect of making the ‘head raising’ totally predicable. The calculation for part B is dependent only on the fake block number. If we had done that for the Constantinople fork, the time bomb would not be going off so soon.

Conclusion

Thanks for reading this far if you got this far. I hope this document finds interested ears. I see a lot of confusion related to the difficulty calc issue (not only in the public, but in the core devs channel and the Ethereum Magicians). I feel people are making this much more difficult than it actually is.

A few simple takeaways: (1) because of its exponential nature, only part B matters as far as the block production is concerned; (2) part A of the calculation can have no detrimental effect on block production and it may actually have a positive effect; and (3) resetting the period or fake block to zero has two benefits: (a) it grants the maximum amount of time in delaying the time bomb, and (b) it makes the re-appearance of the bomb very predicable.

Please let me know what you think of this paper. I hope I’ve helped explain something that I know about pretty well.

Thomas Jay Rush owns the software company TrueBlocks, LLC whose primary project is also called TrueBlocks, a collection of software libraries and applications enabling real-time, per-block smart contract monitoring and analytics to the Ethereum blockchain. Contact Rush through the website. Send donations to 0xf503017D7baF7FBC0fff7492b751025c6A78179b.