Ethereum’s Issuance: minerReward

First in a series about issuance

Recently, there was a dustup on Crypto Twitter (started here, carries on here) about Ethereum’s money supply. The claim was made that Ethereum’s money supply was not easily available, nor was it widely agreed upon.

News flash: Both of these claims are right.

At one point, our project, TrueBlocks, was mentioned, so I thought I’d write an article (which has grown into two articles and a code base) exploring the issue.

While the work we present here doesn’t necessarily make the numbers easier to get (fix the node!), the numbers are accurate to 18-decimal places and verified to the on-chain account balances at every block. We used TrueBlocks to do that.

Going Back to Basics

To really dig in, we are going to go back to basics. In Ethereum, that means reading the Yellow Paper. We’ll look closely at Section 11.3, as that section describes the issuance of new ether, or as they call it, the Reward Application.

I will present each sentence from Section 11.3 verbatim, and then show a copy of the equations associated with that sentence, then translate those equations into English. Finally we translate the equations into purposefully simplified C++ code using TrueBlocks. TrueBlocks helps us extract and analyze the data as part of the code base.

Section 11.3

We start with the introductory sentence of Section 11.3:

Since there are no equations, we will skip right to the English language re-write to get started:

At every block, the balances of at least one, but possibly more, accounts are issued new coins.

Before going too far, let’s define the word _“ommer.” “_Ommer” is a gender-neutral word for the sibling of a parent. Your aunts and uncles are ommers. The words “ommer” and “uncle” are used interchangeably in this article. Every block has a list of zero or more ommers. There are at most two ommers in a given block (Section 11.1).

Increases to two different account balances are mentioned in the above sentence.

We will call the first increase — to the account balance of the beneficiary of the block reward — the blockReward. Every block has a blockReward. blockRewards are discussed in this article.

We will call the second increase — to the account balance of the beneficiaries of the ommer rewards — the uncleReward. Not all blocks have uncles; therefore, not all blocks have an uncleReward. uncleRewards are discussed in the next article.

The Crux of Section 11.3

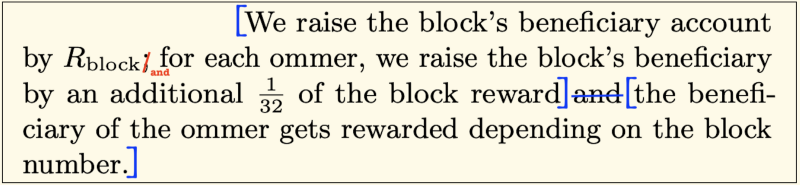

The next sentence in Section 11.3 of the Yellow Paper is the crux of the calculation. This sentence describes Ethereum’s issuance fully:

While this sentence is complete, it is terribly un-grammatical, making it difficult to understand.

It has two main clauses, identified with blue brackets, and, worse, the first clause contains two thoughts smashed together (and separated incorrectly by a semicolon). These two thoughts should be combined, as I’ve done with the red correction.

Luckily, the two parts of this sentence correspond to the two types of balance increases mentioned earlier. The first clause is referring to the reward given to the beneficiary of the block reward (blockReward). The second clause refers to the beneficiary of the ommer rewards (uncleReward).

blockReward

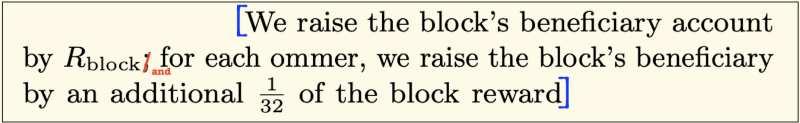

Looking at the first half of the second sentence of Section 11.3 (as corrected)…

…you should be able to see that this is referring only to the beneficiary account (that is, the winning miner). It says that the winning miner’s account balance is raised (i.e. coins are issued to**)** by an amount designated byR-block (which we call baseReward below) plus 1/32 of that amount for each uncle in the block.

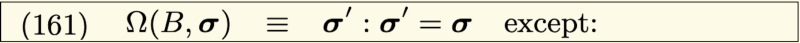

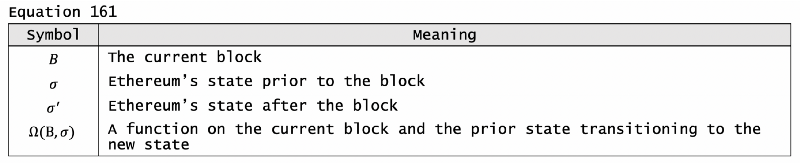

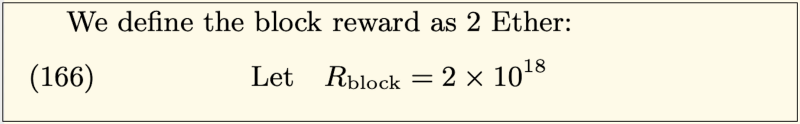

The Yellow Paper summarizes the production of this amount with two equations: Equation 161 and Equation 162. Equation 161 says:

where…

In words, Equation 161 says, “Omega is a function taking the current block and the state prior to the current block and transitioning to a new state which remains unchanged except for…what appears in Equation 162”:

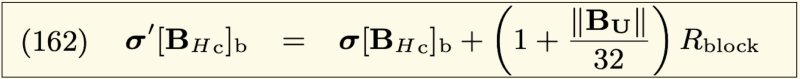

where…

Equation 162 is saying the “the account balance of the beneficiary (miner) increases by the baseReward plus 1/32 of the baseReward for each uncle.”

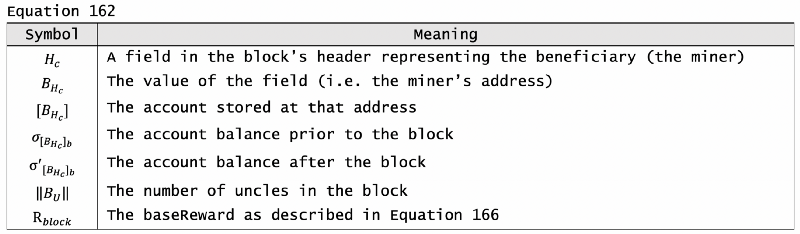

baseReward is defined in equation 166:

which is slightly wrong as it ignores the change in the block reward at the Byzantium hard fork (from 5 ether to 3) and then again at the Constantinople hard fork (from 3 ether to 2). This omission is accounted for in the code.

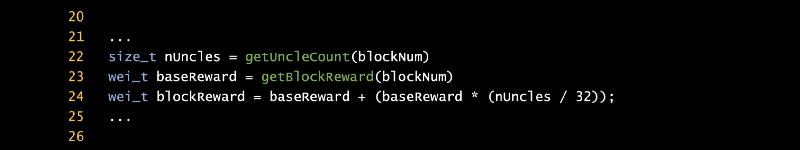

All of the above mumbo-jumbo can be written in three lines of code:

Note that if there are no uncles, blockReward is identical to baseReward. If there are uncles, blockReward is increased by the baseReward multiplied by 1/32 for each uncle. Some people, including us, call this additional increase the nephewReward. (Appropriately, a block is sometimes called a nephew if it has an uncle.)

As crazy as it may seem, this is the entire calculation for blockReward. We will look at the uncleReward in the next article.

The two functions, getUncleCount and getBlockReward, (shown green in the code above) are part of TrueBlocks and remain to be explained.

getUncleCount is a straight-forward passthrough to Ethereum’s RPC call eth_getUncleCount. The interested reader is referred to the documentation for that function.

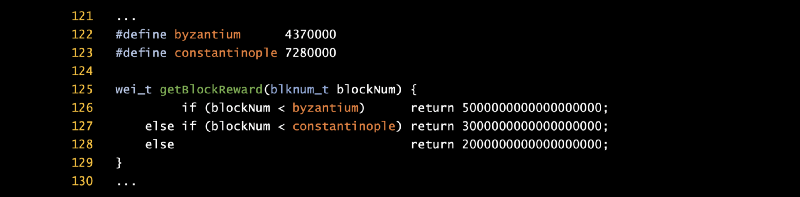

The getBlockReward function is equally simple, as it is a constant function of blockNumber. Here’s the code for getBlockReward, which returns the result in wei:

On review, this function would have better been called getBaseReward.

Previously, I mentioned that blockReward was only one part of Ethereum’s issuance calculation. The other part, called uncleReward, is described in the next article.

Support Our Work

I wish to thank Meriam Zandi for her help in this article.

Help us continue our work. Visit our GitCoin grant page here: https://gitcoin.co/grants/184/trueblocks, and donate today.

Or, if you’d rather not expose yourself to scrutiny, and you’d still like to donate, send ETH to 0xf503017d7baf7fbc0fff7492b751025c6a78179b.