Defeating the Ethereum DDos Attacks

Ignoring things that can be ignored

I spend a lot of time looking at historical Ethereum transactional data. I do this by scanning the chain using TrueBlocks.

If you’ve ever done this, you will be familiar with a certain set of transactions that take a very long time to process. These transactions happened between blocks 2,286,910 and 2,717,576. They are a pain in my a$$. See here.

In a surprisingly effective attack, some evil genius took advantage of an underpriced opcode to create millions of dead Ethereum accounts. This had the effect of significantly bloating the state database, but more importantly for our purposes it created tons of transaction traces.

Until recently, if we were scanning the Ethereum database (especially if we were scanning this section and looking at traces — which TrueBlocks does all the time), we had to wait many hours (perhaps even days) while Parity delivered the traces. We could have cached these traces, but our goal has always been to create a minimal impact on the target machine (this helps us stay decentralized), and we never write data without thinking about it careful. With the solution we present below, we can now effectively choose whether to scan, skip or cache these transactions. This post discusses how we did that and how we now routinely scan very quickly through this difficult portion of the data.

Short History

The morning of DevCon 2, there was a hack against the Geth client. The Ethereum developers responded quickly, and fixed that hack, but a few days later another attack occurred. This second attack went on for more than a month and is described here. In response, the Ethereum devs conducted two hard forks: Tangerine Dream (EIP150) and Spurious Dragon (EIP 161). As one would expect, the hard forks did not change existing data. Instead, they changed the way the client code works so that, at the end of a transaction, if an account has been “touched” during that transaction, and the account would otherwise end up dead, the account is now removed.

The attacker created millions of useless accounts across thousands of transactions prior to the forks. Because the hard forks do not actually remove the dead accounts directly, an off-chain process was initiated to ‘touch’ these accounts so they would be removed. This worked, but it created a second huge amount of ‘cleanup’ transactions each with its own large set of traces. Needless to say — this entire section of the blockchain — from the start of the hack to the end of the cleanup — is ugly and very bloated (which translates in our world to “slow” which we hate!).

Let’s Go To The Data

As I said, these troublesome transactions are especially annoying if you want to view the traces (which TrueBlocks does all the time). We struggled with this problem long enough. We needed a solution.

The first thing we did was to gather some data. We scanned the first 3,500,000 transactions. At each block, we looked at every transaction and counted the number of traces generated during that transaction. (This took a very long time).

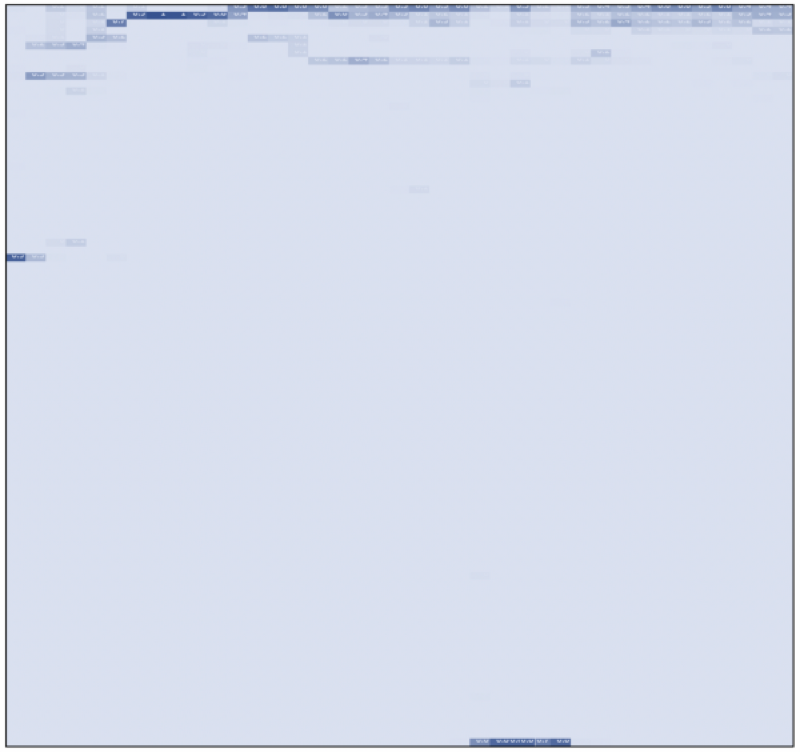

From this data, we created a heat map showing how frequently certain numbers of traces were generated per transaction for each 100,000 block section of the chain. The columns represent rising block numbers starting from zero and going up to 3,500,000. (There are 35 columns in the below chart.) The rows range from zero traces to 150 or more traces in a given transaction, and each cell in the table represents the count of transactions with that many traces.

Light blue represents a small number of transactions in that portion of the chain with the given number of traces. Darker blue represents an increasing number of transactions in that section with the corresponding number of traces. At the top of the chart the dark blue rows represent transactions with anywhere between zero and ten traces. You can see that most transactions, across the entire history of the chain, have few traces. While early blocks seem to have more transactions with two traces, transactions in more recent blocks appear to have a growing number of traces. We think this indicates growing use of smart contracts compared to the eary chain.

We suppose the early blocks with two (and the very early blocks with around 35) traces are experimentation on the early chain when the price of ether was miniscule.

Do you notice anything else of interest? Do you see that dark blue box at the bottom-middle of the chart?

The Fall 2016 Ddos attack stands out like a sore thumb (i.e. there are 1,000s of transactions with many 1,000s of traces in that region). Here was our solution. We can very clearly and easily box in the troublesome transactions. Now that we’ve identified them, we needed a way to skip over them.

Writing Code that Skips Ugly Transactions

It turns out, the solution to our problem was relatively simple. What we did is identify any transaction between 2,286,910 and 2,717,576 that had more than 1,500 traces. First, we needed a way to figure out how many traces a transaction had without querying the traces (querying the traces was the problem after all).

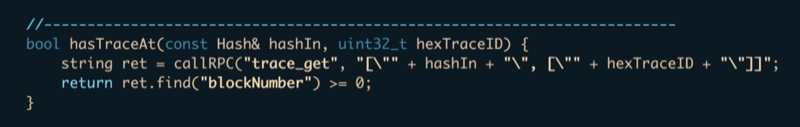

Luckily, Parity’s RPC provides a function to query a single trace. We use that to decide if the transaction has or does not have a trace at a given location:

For example, calling hasTraceAt(hash, 4) would return true if the transaction at hash had five or more traces (zero-based index).

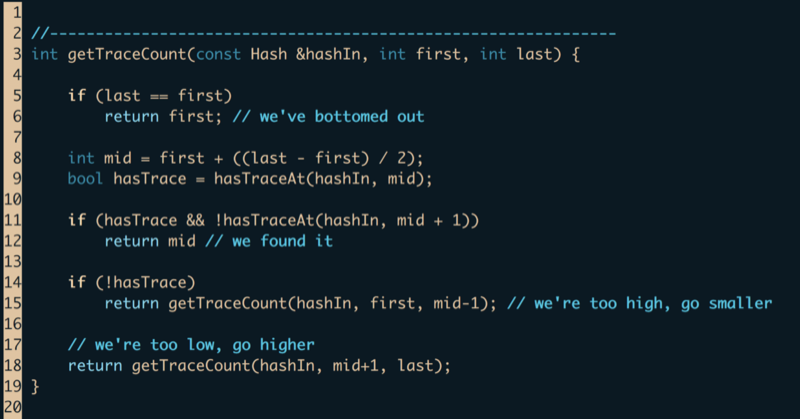

Next, we needed a way to get the number of traces given a transaction hash without querying the entire trace (again, querying the entire trace is exactly the problem). We wrote the following recursive binary search getTraceCount which finds the location where trace n exists but trace n+1 does not. n is then returned as the number of traces in the transaction.

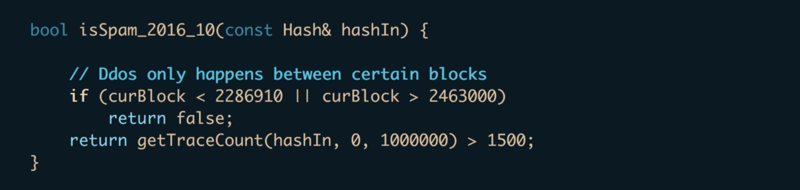

From here, it was a simple matter to write the function isSpam_2016_10 which returns true if the transaction has more than 1,500 traces and occurred during the period of interest. Our calling code can now be configured to decide which transactions to fully trace (and/or cache) without having to wait the “forever” amount of time for Parity to return the traces.

The following list of accounts, while not definitive, were found to be in some way involved with the Ddos either through cleaning up process or through initiating them. We sometimes also use this list of accounts to simply skip over transactions if the the particular analysis requires that we do so. In some cases, we scan these accounts, in many cases we don’t.

//— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — -

const Address relatedAccounts[] = {

// These smart contracts carried

// out the stateClear process run after

// the hard fork to clean dust accounts

“0xA43EBd8939D8328F5858119a3fb65f65c864c6Dd”,

“0xE9c9068240D8450Da314f60804deBFc194B72309”,

“0x0e879ae28cdddeb31a405a9db354505a5560b0bd”,

// These smart contracts were involved in the DDos

“0x6a0a0fc761c612c340a0e98d33b37a75e5268472”,

“0x7c20218efc2e07c8fe2532ff860d4a5d8287cb31”,

“0x10fa9f37f646bb353945fe90d41a44e1c60745fb”,

“0x822f505e0174ef22d2a774cb80a855ffd27ae3bf”,

“0x59493d3fc7a8522253b8be0d168b8ad22ff85177”,

“0xba0577e1419237fd4b8c14a6f49984f6466b5996”,

“0x4943e4bd90d7ff8bafe1bd202e08907903ebdb66”,

“0x3898d7580aa5b8ad8a56fcd7f7af690e97112419”,

“0x8a2e29e7d66569952ecffae4ba8acb49c1035b6f”,

“0x9f58ef5d703973ba98dfa7a9bdecabecf13a0ec3”,

“0x8428ce12a1b6aaecfcf2ac5b22d21f3831949da3”,

“0xaa7c4ca548ffc77a42b309aaaea40a1bd477ac70”,

“0x2213d4738bfec14a2f98df5e428f48ebbde33e12”,

“0x7c1cf1f9809c527e5a6becaab56bc34fbe6f2023”,

“0xde21bc367afe7a3705a15255ff46a5ae91e8341c”,

“0x1fa0e1dfa88b371fcedf6225b3d8ad4e3bacef0e”,

“0xd3e32594cedbc102d739142aa70d21f4caea5618”,

“0xfb34db0651ab62d73a237fcf1aa1057ceb1f6229”,

“0x40525ac2fe3befe27a4e73757178d4accfef71da”,

“0xe25e422e3f9e9374a3d8a75451c790d48fb33218”,

“0xb09f8a62c6681b0c739dfde7221bfe8f2da3f128”,

“0x4b8f3b2e935a341929c0a4efe5110314f39dea73”,

“0x0c40cf6dd1b74c6edfc4729021a11f57b31e3c27”,

“0xf9110f7f0191317eb4bcd96e80d86946eb5426c5”,

“0x1dacf33da596a743be75933ce066f9c6e142a460”,

“0xb233cb2f0dce57a56bf732767f45ffc8650186c5”,

“0xb233cb2f0dce57a56bf732767f45ffc8650186c5”,

“0x25612c41773cb96167854ff72b1c2d7dc8973e2f”,

“0xd6a64d7e8c8a94fa5068ca33229d88436a743b14”,

“0x7fc03bd9e44c37bc2d111dc2154da781dbba7c24”,

“0x45faec35e32676568ad827aea17fb7431ef390bc”,

“0x29446e8d2f0ca2e7fd9e46665e80fc2cd55bf262”,

“0xab90c4455d32f1e579152f52377e3cbf9b3cc37b”,

“0x0c40cf6dd1b74c6edfc4729021a11f57b31e3c27”,

};

const uint32_t nSweepers = sizeof(sweepers) / sizeof(Address);

What We’re Working On

TrueBlocks is a software package that allows us to deliver much faster and more usable Ethereum blockchain data to our users. While this same task can be accomplished by using (admittedly useful) 3rd party websites such as Etherscan, we are a fully-programmable and fully-decentralized solution. This means we’re writing software that runs on your machine.

Running an Ethereum node is difficult enough. For this reason, we need to be certain that TrueBlocks imposes a minimal burden on the machine. A naive implementation would index the data and save a duplicate copy of the blockchain chain into a local database. TrueBlocks doesn’t do this. Instead, we accomplish speedy data (tens of times faster than querying the local node, hundreds of times faster than querying a remote node such as Infura, and nearly as fast as a 3rd party website API such as Etherscan) but do this by placing less than 3GB of additional data on the hard drive. We’re making progress every day and hope to start pushing out product soon.

Support Our Work

We’re interested in your thoughts. Please clap for us and post your comments below. Please consider supporting our work by sending a small tip to 0xf503017d7baf7fbc0fff7492b751025c6a78179b.

Thomas Jay Rush owns the software company TrueBlocks whose primary project is also called TrueBlocks, a collection of software libraries and applications enabling real-time, per-block smart contract monitoring and analytics to the Ethereum blockchain. Contact him through the website.