A Too-Often Neglected Aspect of Smart Contract Security Auditability

Write better Solidity events

In the wake of The Great DAO Debacle of 2016™, there have been many articles and blog posts concerning the need for the community to write more secure Solidity smart contracts.

One such article is Writing More Robust Smart Contracts by Elena Dimitrova of Colony.io. Here, Dimitrova discusses the use of function modifiers to verify — prior to a function’s execution — both the initiator of the transaction and the input to the transaction. The gist of the article, if I may summarize, is that by using readable and easily understandable modifiers, one may increase readability and help to insure that the function will execute only under certain conditions. This is an excellent idea, obviously, and one that all of us should follow.

Another truly excellent article is Onward with Ethereum Smart Contract Security by Manuel Aráoz an editor at BitCorps. The author discusses numerous well thought out ideas on how to better secure one’s contracts: fail [in a function] as early as possible, favor pull over push payments, limit the amount of funds [in a contract], and many other useful suggestions. You should read that article. It’s accessible and quite well done.

At one point, Aráoz’s says, “Security comes from a match between our intention and what our code [is] actually [allowed] to do. This is very hard to verify, especially if the code is huge and messy. That’s why it’s important to write simple and modular code.” I would make an addition to this comment thus: “…it’s important to write simple and modular code…and make it easy for someone to later audit what happened…”

In this article, I will discuss a too-often neglected aspect of smart contract security: auditability.

The Great DAO Debacle of 2016™

It’s not necessary for me to spell out in detail what happened to The DAO. Let’s just say that the un-hackable, impenetrable, immutable DAO was both hacked and penetrated and then stolen from (by a bad guy), stolen from again (by a group of good guys), refunded (through the withdraw contract and a hard fork) and now lies nearly dormant.

Unattributed pseudo-quote from Ethereum’s founding fathers: The Ethereum blockchain is immutable (not in the sense that once a transaction is processed it will never change, but more in the sense that this is how we would like you to think of it…)”

All of this is water under the bridge, but ever since the hack, I’ve been trying to re-create what happened with the DAO. I’ve been trying to verify that the number of tokens purchased was correctly recorded. I’ve been monitoring the DAO Withdraw contract to see how much of the community’s ether has been successfully returned. Not as much as you might think. I’ve also been monitoring the DAO’s curators.

My two sources of information are the transactions initiated against the DAO, and the events generated as a result of those transactions. I’m finding recreating what happened to be very difficult because there appears to be a significant amount of missing or difficult-to-come-by information.

The Need for Auditability

Every user-initiated interaction with a smart contract creates a transaction on the Ethereum blockchain. These transactions are easily tracked on popular websites such as http://etherscan.io. A transaction is created even if a function’s execution fails (for example, because it ran out of gas).

During the execution of many of the transactions, events are also written to the blockchain; however, as we shall see, this is not always the case.

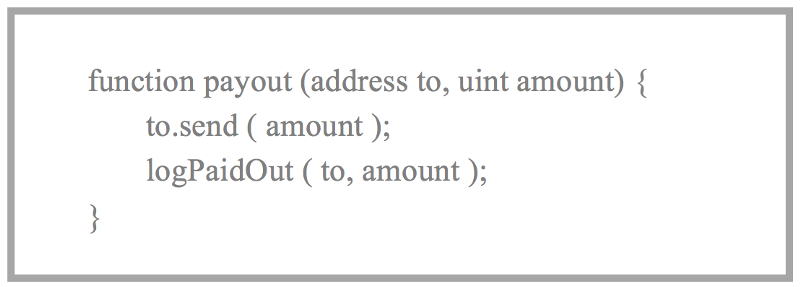

Using a purposefully silly example, say you had a function that paid out ether to anyone who asked (obviously a ridiculous idea, intended only to entertain). A naive implementation might look something like this:

In this case, a record of the transaction is laid on the blockchain as well as an event (or, as I think it would be better called, a log entry) would also be written with the same information.

Notice, however, that there is a mistake here. Besides the obvious fact that anyone who wanted to could simply take all the ether, the function writes a log entry to the blockchain even if ‘send’ call fails. The contract’s author has neglected to check the return value of ‘send’. Before you scoff at this example, take a look at this line from the White Hat ETC Refund contract. Before it was fixed, it did exactly this. Edit: this commit is gone now. It used to be here. https://github.com/BitySA/whetcwithdraw/commit/731b6c0f31f2c4781411f47e2248895c696ea65b#diff-6abf7d6326637cc6a3023c6de66a5196L1.

This is one type of ‘auditing error’ or ‘logging error’ that I’ve identified as I’ve tried to understand exactly what’s been going on with the DAO. I present a few more in order of increasing severity.

Too Much Information

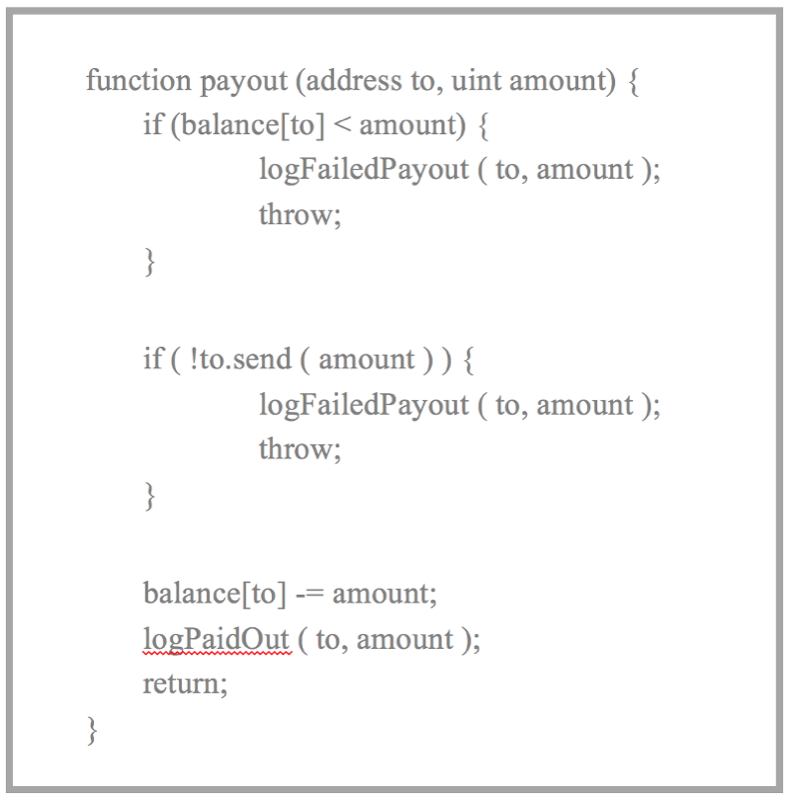

As I mentioned above, for each function invocation, a transaction is laid down on the blockchain even in the case of an error. These ‘in error’ transactions are identified with a flag called ‘isError.’ An example of providing too much information in a function would be something like this:

I think, in this case, the contract’s author is over-reporting. No new information is given by the two log entries reporting the failure. The transaction carries with it the to and the amount already, and the absence of the logPaidOut message and the isError flag indicates a failure. There’s a balance to be won in reporting for auditing purposes. Try not to pollute the audit trail by providing redundant information. You’ll just have to sift through it later.

Furthermore, simple function modifiers such as those discussed in Dimitrova’s article, if they contained a lot of error logging, would be made more difficult to understand, thereby defeating one of their purposes: readability. Finally, a contract’s state is not changed when an exception is ‘thrown.’ Perhaps it makes sense to only generate log entry when the state is changed, and refrain otherwise.

Not Enough Information

Another way you might mis-handle the auditing aspect of your smart contract is to not provide enough information in your log entries. For example, if logPaidOut only recorded the to account and neglected to record amount, that would be an example of providing too little information. While it would be possible for an auditor to figure out the amount, it would be much easier to simply include it to begin with.

Not providing enough information is not as bad as not providing any information at all. In the above example, if the logPaidOut entry was removed, there would be no way for the auditor to figure out if the transaction succeeded or failed in sending the ether. While I am not 100% certain of this, I believe that without a ‘throw’ the error flag would not get set on this transaction. Without the isError flag, and without a log entry, I don’t know how one would properly audit this. I may be missing something.

Incorrect Information

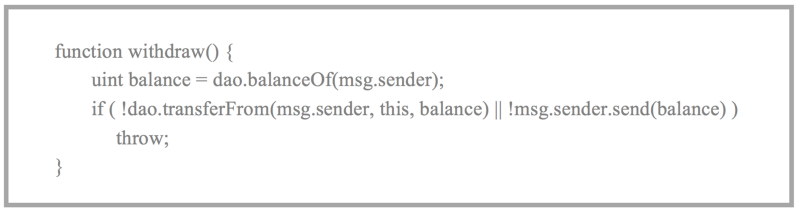

The worst type of auditing error is providing incorrect information. One possible example appears in a familiar contract that many of you may have already interacted with: The DAO post-fork withdraw contract. Here’s code from that contract:

When I first looked at this, I was convinced this was an example of reporting incorrect log information, but I have been since corrected by Mr. Nick Johnson (see his comment below). I initially thought that if the transferFrom call succeeded on the DAO but the msg.sender.send failed an event would have been written during the transferFrom call to the DAO’s log. Obviously, this would have been bad since the ether was not actually sent.

Mr. Johnson informs me that in this case, because of the throw, the entire set of state changes (including parts of the transaction initiated in another contract — even if that contract call succeeded) are wiped out. This, of course, is a good thing.

So what would be an example of an ‘incorrect information’?

There’s the obvious bug scenario where, for example, you have two events with similar names and you incorrectly use one over the other. I also consider missing or misleading log entries as errors.

The above examples illustrate where incorrect or incoherent information can be laid down on the blockchain making it nearly impossible for an auditor to recover exactly what happened.

Conclusion

I’ve heard it said that a contract is worthless when everything is working as it’s supposed to do. How many times, for example, have you read your pre-nuptial agreement? I know I don’t read mine — not to mention the consequences if my wife found me reading it.

A contract matters most when things fall apart. Being able to audit something takes on more urgency when one it trying to figure out exactly what went wrong with something.

When you’re designing your smart contracts, in addition to adhering to all of the recommendations from the many security-related articles, you should take great care in designing your logging system. Think about how you will audit your contract’s behavior if something goes wrong. Don’t be redundant; don’t be overly terse; but most of all make sure to lay down correct information.

Thomas Jay Rush has owned and operated TrueBlocks, LLC for many years. After a four-year hiatus, during which time he pursued a career as a poet — not a good idea — Rush returned to software engineering with a passion for Ethereum. He now spends all day, every day and much of the wee hours of the night obsessed and working on EthSlurp, a tool designed to aid smart contract auditors. Contact us if you would like us to help you with your smart contract needs.