A Time Ordered Index of Time Ordered Immutable Data

Adventures in indexing the Ethereum blockchain

Did you ever notice that the only way to get the history of an Ethereum account is to visit a fully-centralized, database-driven, old-fashioned web-2.0 website?

Every time I use one of those sites (and I use them all the time), I think to myself: They’re watching me. They’ve attached my IP address to my address and in the future, they will wildly invading my privacy…but I need them…

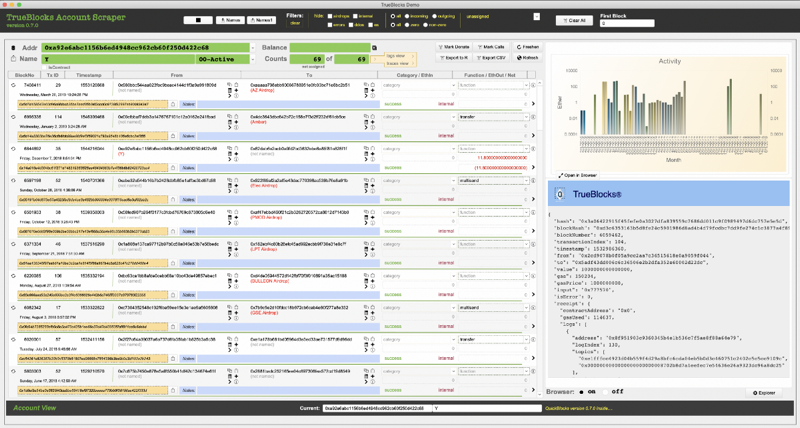

Recently we demoed a fully decentralized blockchain explorer built on TrueBlocks. (Check it out here.) At the core of our explorer (which runs on commercial-grade hardware) is an index of Ethrerum addresses. This article discusses how we built the index, the difficulties we ran into, and why it’s way more complicated than you may think to share it — especially if you want to avoid becoming an old-fashioned, outdated, web site destined to invade people’s privacy.

The Trouble With Time Ordered Data

As everyone knows, blockchains are not databases. Blockchains are time-ordered logs of transactions. Each transaction is laid down on the chain as it happens, and it’s stored (at least conceptually) on disk in that same order. The time-ordered nature of the data makes it possible to fully represent each block (and the history of all blocks prior to that block) with a short, immutable hash. Time-ordered logs and immutable, hash-denominated data go together like math and poetry.

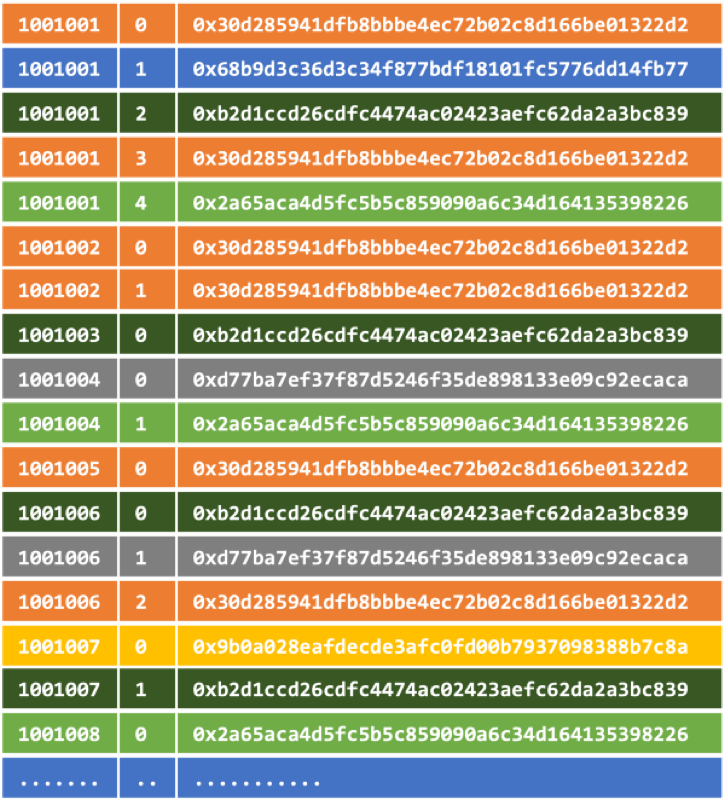

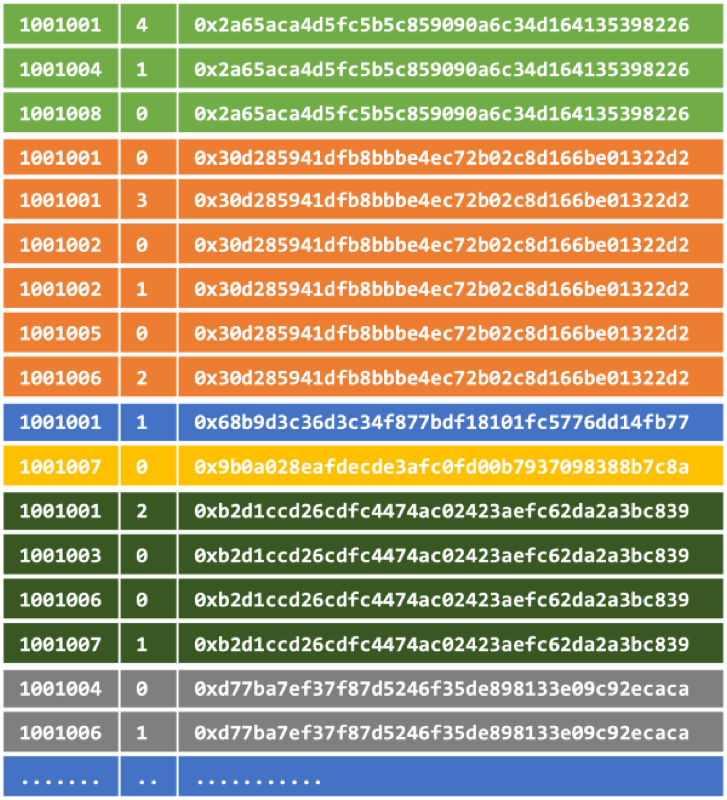

Using the Ethereum node’s RPC interface, TrueBlocks retrieves each block as it appears, requests every transaction in that block, and then requests every receipt, every log, and every trace in those transactions. We parse all this data extracting anything that may appear to be an address — we’ll write about this process in a later post — and given this collection of addresses, sort it by transaction_index within block_number within address and then write that sorted list to disk.

If we went no further than this — simply creating sorted lists of address appearances per block — that would actually produce a significant speedup compared to scanning the time-ordered log by itself. Of course, we want to do better than this. We can, for example, produce larger, consolidated, sorted lists which would be way faster to search than single blocks.

Our scraper does exactly this. It keeps track of the total number of appearances it’s seen, and, as soon as there are a certain number of records (currently 500,000), combines them, sorts them by address, and stores the sorted index in a single, much larger, file.

This greatly increases the speed of up subsequent searches for an address — of course it does — that’s the nature of a database index.

Over the first 8,120,000 blocks, our process has created around 3,000 such sorted lists (“chunks” as we call them). Each chunk contains approximately 500,000 appearance records. An appearance record is <address,block_number,tx_id>.

You may ask why we don’t simply store the index in an old-fashioned web 2.0 database and distribute the results of querying that index using an old-fashioned web 2.0 API? I’ll try to explain why this is not what we want to do. Hold on to your hat.

Why Not Just Build a Web 2.0 API to Distribute the Index?

Decentralization.

What’s the Problem with Web 2.0?

Why does web 2.0 suck? Let me count the ways: privacy invasion, unverified data, fragility, single point of failure, data/user capturability, user lock-in, privacy invasion, the rich-get-richer problem. The list is very long. But, the worst problem — and one that is quite difficult to explain — is that web 2.0 does not scale the way we need it to if we want to build a decentralized world.

In fact, current, old-fashioned, web 2.0 blockchain explorers will lead us further and further away from a truly decentralized world.

The architecture of web 2.0 blockchain explorers is to first extract all the data from the chain, put it in a web-scale database, index the data ten ways to Sunday, and finally deliver not the index of the data, but the underlying data itself. This is directly in opposition to decentralizing the data.

The provider of such a service is effectively saying to the user:

D_on’t worry your pretty little head about getting the data yourself, we will get it for you. Be our guest. Focus on building your application. We promise it will fine. You can trust us._

But this is exactly the opposite of the direction we want to be headed.

The size of the extracted data this model produces continually grows (probably exponentially), therefore, the cost of delivering that data will grow. This, obviously, will force these data providers to monetize their users. And, in my opinion, this will lead to the exact same list of problems I mentioned above, particularly user lock-in and privacy invasion.

We can do better.

Recognize the Importance of Immutable Data

The blockchain’s data is immutable. We not only need to resign ourselves to this fact, but we should embrace it. There are no two ways around it. Immutable data does not like to be indexed. Every time one inserts a new record into an immutable list, one changes the hash that’s generated when that data is stored (in IPFS for example). So it seems that you can’t have both immutable data and a sorted index.

To solve this problem, one simply has to stop adding items to the list (as TrueBlocks does by creating time-ordered chunks of account-ordered indexes of the time-ordered ledger). In this way, one gets a compromise between immutable data and an easily-searchable, indexed database. It turns out this is enough to build an API which is enough to support a whole suite of applications including a fully decentralized blockchain explorer:

So What is TrueBlocks Delivering?

We’ve discussed this in two recent articles (here and here), so I won’t go too deeply into it, but fundamentally TrueBlocks is building a system that creates partial indexes of address appearances across the blockchain. These partial indexes, or chunks as we call them, are stored in separate files partitioned each time the number of records overtops 500,000.

We chose this number of records arbitrarily but chose it because we wanted to balance the size of the chunks on disk (around 8MB each), the time it takes to produce new chunks, and the number of files produced (around 3,000 by block 8,120,000).

The time it takes to produce new chunks bears a bit of explanation.

If our index is far behind the tip of the chain, we can process many blocks at the same time in parallel. Once we catch up to the tip, things change.

When we’re trying to catch up, we move as quickly as possible, and in fact, we easily scrape the entire chain and catch up in about a day and a half. (This used to take more than three weeks, but recently we re-wrote the scraper in go and now take advantage of parallelism which hugely speeds up the process. Thank you, Nate Rush!) It takes about 45 seconds to produce each new chunk of the index when we’re playing catch up. (3,000 chunks at 45 seconds each → 135,000 seconds → 2,250 minutes → 37.5 hours → 1.56 days.)

Once we’re caught up, the story changes completely. Now, the process spends nearly all its time waiting for new blocks. At current usage rates, the Ethereum chain produces about 450 unique address appearances per block. (An address can appear multiple times in a block if it appears in different transactions, but only once per transaction.) In order to accumulate 500,000 records to build a new chunk, we need about 1,111 blocks. Blocks appear about every 14 seconds → 4.285 blocks per minute → 259.30 minutes to produce 1,111 blocks → about four and a half hours to produce a new chunk.

Chunks — very importantly — are immutable, never changing, able to be published to IPFS and shared with the entire community — forever!

So, Seriously, What is TrueBlocks Delivering?

We are going to deliver an API that will run either locally against your locally-running node, remotely under docker against something like a dAppNode, or even remotely as an old-fashioned web 2.0 database-driven website.

In all three cases, the API will not deliver the JSON data that the user wants when they say, May I have all transactions on account 0x1234…. Instead, our API will deliver the hashes to the chunks of the index that the user needs to search the node directly to get the data they want.

User to TrueBlocks API: curl [http://endpoint/list_transactions/address](http://endpoint/list_transactions/address)

A simple API query that returns somewhat unexpected results.

API to User: [ { “hash”: “QmXREJnqJ…”, “range”: “6517955–6519510” }, { “hash”: “QmQMBTt…”, “range”: “8102894–8104450” } ]

The API returns hashes to the index chunks the user needs to search. In the great majority of cases, this is a very short list because regular users interact only periodically and then in short bursts. A regular user, querying for hisher own accounts, may get five or six hashes.

For heavy users of the chain such as popular dApps or exchanges, the list will be much bigger (but not larger than 3,000 entries). This is exactly how we want it to be because regular users should not have to shoulder the burden for heavy users.

User to IPFS: for each hash { ipfs get ${hash} -o ${range}.bin ; pin ${hash} }

The user brings the chunks locally to their own machine. It’s impossible to capture them from here on out. They have all the data they need to find the history of that account — and — that data will never change. As long as they themselves keep it, they can never be captured.

The

_pin ${hash}_part of the above line accomplishes this. By default, we want users to copy the index chunks locally (this will also increase the speed of searching) and then pin their own chunks.

This makes subsequent queries to IPFS for that same chunk, system wide, all the more fast since more copies of that file are more easily located. In this way, everyone shares the burden of carrying the index in proportion to their use and the effectiveness of the system grows with the number of users (i.e. network effect). Heavy users carry more of the burden, as they should. Lighter users naturally carry less of the burden, which, to me, seems fair.

User to chifra: chifra export address

Chifra read the locally cached chunks of the index and, among other things, exports records to JSON, TXT or CSV. It does this by reading the index chunks, extracting appearances for that address, querying the node for details of the transactions, caching the returned data and then exporting the data to the screen or a file. The caching is important because querying the node and parsing the JSON result can be really slow, reading from a local binary cache is super fast.

Upshot

TrueBlock shares hashes of indexes of appearances of addresses on the Ethereum blockchain. These indexes “releases” the data from the node making it possible to build useful, fast, responsive applications in a fully decentralized way.

By sharing hashes of immutable IPFS files we purposeful relinquish the ability to ever take them back. We will never be able to say, We’ve captured you. If you wish to continue to use our data, you must pay us (or we’ll extract payment by invading your privacy).

We gave up this ability on purpose because we believe that if the data on the blockchain is not fully free and open in the same way the open-source software code is, the system will ultimately fail.

We will be rolling out, documenting, and writing about our work a lot over the next few months. We’re going to Berlin in August, so if you would like to discuss our work, please reach out. If we can get a ticket, we’ll be at DevCon as well.

Support Our Work

We’re interested in your thoughts. Please clap for us, tweet about us, and post your comments below. Consider supporting our work. Send us a small (or large) contribution to 0xf503017d7baf7fbc0fff7492b751025c6a78179b.

Thomas Rush owns the software company TrueBlocks, LLC whose primary project is also called TrueBlocks, a collection of software libraries and applications enabling real-time, per-block smart contract monitoring and analytics to the Ethereum blockchain. Contact him through the website.