A Eulogy for The DAO — Part II

Second in a series

Introduction

In this second installment of a multi-part series of articles analyzing the nearly 170,000 interactions with “The DAO” smart contract, we discuss the contract’s “Creation Period.” Previously, we presented an overview of The DAO’s lifespan. In that overview, we identified four distinct timeframes: the Creation Period, the Operational Period, the Post-Hack Period, and the Recovery Period. In this installment, we focus our attention on the Creation Period. Future installments will analyze each of the remaining three periods separately.

Creation Period

The DAO’s creation period lasted for 28 days from April 30, 2016 01:42:58 AM (block 1428757) when it was deployed to May 28, 2016, 09:00 (block 1599205). According to the EtherScan website, more than one billion DAO tokens were created.

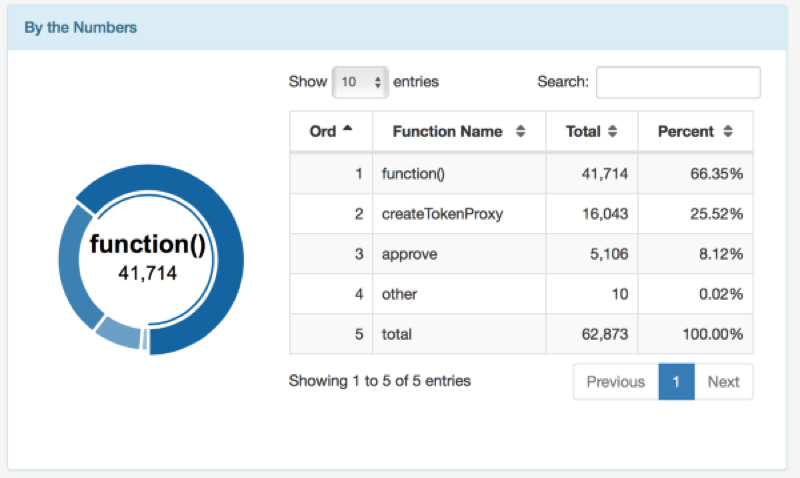

Because much of the smart contract’s functionality was disabled during creation, three functions dominate the logs during the period: function(), createTokenProxy(), and approve().

We find that nearly two-thirds (66.35%) of the 62,873 interactions during the Creation period were calls to the default function. A call to the default function, function(), occurs when a contract is sent ether directly. The code of the default function is quite simple: either it creates tokens by calling createTokenProxy(), or, if called after closingDate but before the end of the grace period, it sends the ether back to the caller, or, if called after the end of the grace period, it keeps the ether. Together, the two functions createTokenProxy() and function() account for 91.86% of all interactions during creation. 8.12% of the remaining interactions were approve() calls, which are discussed below. 0.02% of interactions were with other, infrequently used functions.

Token Creation

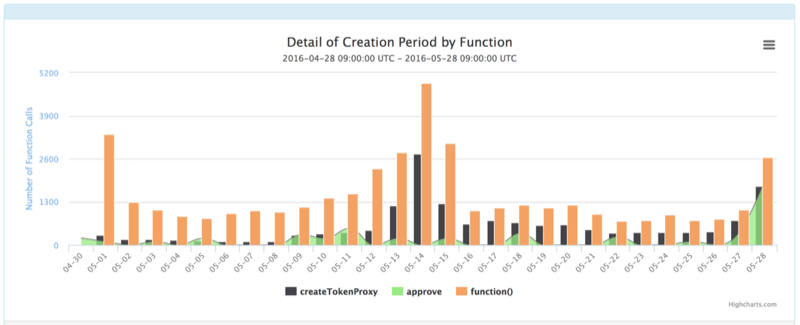

In the bar chart below, we present the number of times each of the three functions was called each day. The initial flurry of activity on the first day, followed by a lessening, followed by a spike near the midpoint of the period, then another lessening, leading, finally, to a period of growing interest, is easily explained, as is the change in the usage of the createTokenProxy() call relative to direct sends of ether.

Many initial purchasers of the DAO tokens had clearly been anticipating its arrival and were ready to act on the first day. These users, one presumes, were more technically adept, which is hinted at by the significantly higher frequency of direct sends (orange bars) compared to createTokenProxy() (black bars) during the first few days of operation.

One might notice that as more purchasers appeared, the difference between the number function() calls relative to createTokenProxy() calls lessens. We believe this is due to the use of tutorials explaining how to purchase tokens. Many tutorials instructed users to use the Mist browser (as opposed to say the ‘geth’ command line interface) and from there to call into the createTokenProxy() interface. Of course, this is only conjecture, but it helps explain the growing relative use of createTokenProxy().

A Simple Mistake Leads to User Confusion

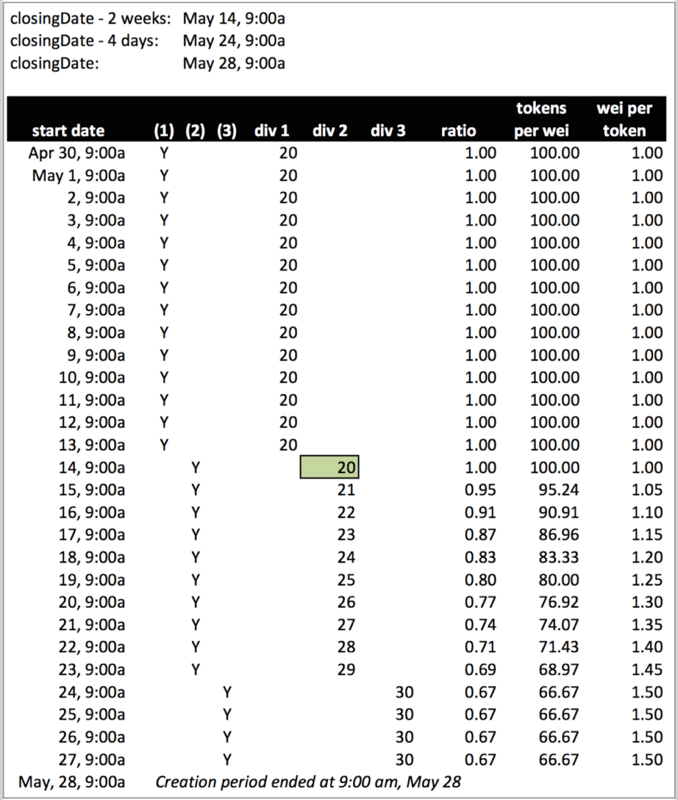

At the start of the creation period a single ether purchased 100 DAO tokens. Midway through the period, that ratio began a steady ten-day decrease until finally reaching 100 DAO tokens per 1.5 ether, where it remained for the last four days of the period. This behavior is explained well in this blog post and is further illustrated in the table below:

This table was generated by analyzing the following code. In the code, createTokenProxy() calls into a function called divisor(), the result of which, when multiplied by 20, gives the token/wei ratio. This factor is then multiplied by the amount of ether sent to the function (msg.value) to arrive at the number of tokens to award to the caller.

function createTokenProxy(address _tokenHolder) {

…

uint token = (msg.value * 20) / divisor();

extraBalance.call.value(msg.value — token)();

balances[_tokenHolder] += token;

…

}

The divisor() code looks like this:

// Return the divisor used to calculate the token creation

// rate during the creation phase. _The number of tokens per

_// wei is calculated as msg.value * 20 / divisor

function divisor() constant returns (uint divisor) {

if (closingTime — 2 weeks > now) {

// The fueling period starts with a 1:1 ratio

return 20;

} else if (closingTime — 4 days > now) {

// Followed by 10 days with a daily creation rate

// increase of 5% return (20 + (now — (closingTime — 2 weeks)) / (1 days));

} else {

// The last 4 days there is a constant creation rate

// ratio of 1:1.5

return 30;

}

}

Looking back at the bar chart above, one may notice the users’ behavior approaching May 15th, the first day of the price increase. As expected, activity increases as the price rise approaches. Notice, however, that the greatest activity occurs on May 14th, a full day before the price increase. (Each bar represents the activity between 9:00 am the previous day and 9:00 am on the current day, so the bar labeled May 14th ends at 9:00 am, May 14th — 24 hours before the first price rise).

The green-enclosed box in the table above helps explain this unexpected behavior, which is due primarily, we think, to an error on the DAO Hub website (see this DAOHub discussion and this reddit post). It seems the maintainers of the DAOHub website read the code wrong and made a miscalculation as to the first date of the price change.

Alternatively, one might say that the software code itself is in error. The somewhat confusing code of divisor() passes through a different path on May 14th (i.e. closingTime - 2weeks). However, oddly, it arrives at the same result (20). It is easy to see why the error on the website was made.

The extraBalance Account

Referring back to the source code above, notice the second line of the createTokenProxy code where the extraBalance account is funded with the amount over the 1:100 refundable tokens of the early adopters. This account was initially intended to hold the ‘profits’ of The DAO, which were later to be distributed pro-rata by token share; however, a decision was taken at some point to refund the original late purchasers with the exact amount of ether they sent. It is not clear, exactly, how that decision was made. It certainly was not voted on by token-holders as some people think it should have been.

Approve Calls

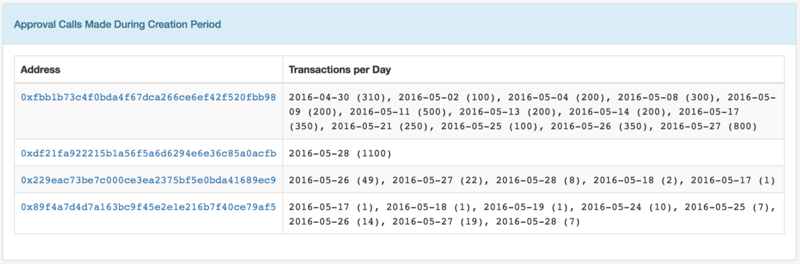

The undulating green area mentioned above represents calls to the approve function, one of the few functions that were not disabled during the Creation Period. We do see something a bit surprising here.

First, the existence of approve calls itself prior to the ability to actually make any transfers is unexpected, at least to this writer.

Secondly, and more surprisingly, is the regularity of these function calls and the fact that they came almost entirely from four addresses. It is our belief these calls were most likely exchanges practicing or testing their software prior to the start of the Operational period.

For most of the month, on a day when the approve function was called at all, it was called an even multiple of 100 times. For one account, the approve function is called 310 times, then 100 times, then 200, then 300, 200, 500, 200, and 200 times every few days. This pattern is revealed in the consistent heights of the green-shaded area above. These ‘100-transaction’ sets were clearly generated by software. This becomes obvious in the table above which is presented without further comment. We shall see in the next installment of our series what these exchanges were preparing for.

Conclusion

Obviously, having raised nearly $150,000,000 US in 30 days, and being the largest crowd sale in history, the DAO’s creation period was a wild success. Ignoring that huge amount of money for a second, we find nothing really surprising in the interaction patterns we see in the data.

The mistake made by the DAOHub website, causing people to buy tokens a day early, is revealed by the data. A lesson to be learned here is to be very careful when reporting on what you think a certain piece of seemingly easy code does.

The effect of disabling many of the functions of the contract until after the creation period is revealed as well.

Overall, though, nothing surprising happens during this first of the four periods of The DAO’s lifespan. Early adopters bought in early, many people waited until the last moment before the price rise to buy in, and many people joined the circus near the end in a clear case of FOMO. As we move into the next three periods with further installments of this series, we think you will agree that the ride gets a bit more bumpy. Stay tuned…

Support our work: Do you enjoy reading our work? If yes, please consider supporting us with a small donation to our tip jar. Also, check out our new website with interactive charts supporting this post at http://trueblocks.io. Thanks for your interest. See you next time.

Notes on the Analysis: Missing from this analysis is the daily value of ether and DAO tokens accumulated. While this information is available, we hope eventually to expand our system to make the extraction of this type of information automatic, particularly given the emerging ERC 20 Token Standard. In the future, we hope to automate the analysis of any and all ERC 20 token-based smart contracts. We therefore did not include the information here, as it would have required hand-generated data. Also missing from the analysis is an accounting for ‘internal transactions.’ Again, we are working on automating this data collection. We believe this omission is not material. According to one analysis, less than 1% of interactions during the period were initiated by smart contracts (that is, less than 1% of the interactions were internal transactions). We do not have the data to support this claim, but we believe it to be true.